23 JANUARY 2012

YOUR WORDS

Readers are invited to add their comments to any story. Click on the article to see and add.

BTN DISTRIBUTION

BTN also goes out by email every Sunday night at midnight (UK time). To view this edition click here.

The Business Travel News

PO Box 758

Edgware HA8 4QF

United Kingdom

info@btnews.co.uk

© 2022 Business Travel News Ltd.

Article from BTNews 23 JANUARY 2012

ON TOUR: The Maplin story

Airports in the Thames estuary are nothing new. They were headline news 40 years ago. David Hurst, these days an aviation consultant, was a young press officer with the British Airports Authority at the time. He now delves into the memory (and archives).

Airports in the Thames estuary are nothing new. They were headline news 40 years ago. David Hurst, these days an aviation consultant, was a young press officer with the British Airports Authority at the time. He now delves into the memory (and archives).

Much of the detail comes from government papers in the National Archives plus the annual reports of British Airports Authority and Port of London Authority (PLA). The name did not change to BAA Plc until privatisation in 1988. The 2011 statistics are those of the Civil Aviation Authority (CAA). Current fuel price is from the International Air Transport Association (IATA) website. There are no surviving archives from the British Airports Authority predecessor to BAA Ltd. PLA archives are in the Docklands Museum though their Maplin boxes have not been consulted and are unsorted.

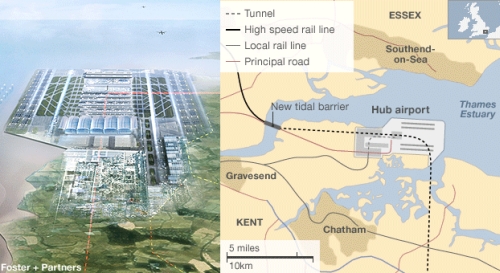

Forty years ago the papers were full of stories about the need for the third London airport. Airport capacity is still news and the Thames estuary is again being looked at as the solution.

Back in 1970 the stories largely resulted from the opinion of the late Sir Peter Masefield (died 2004 aged 91), a lifelong civil aviation businessman, who, depending on your point of view, was either a far-sighted visionary or simply got his figures wrong.

It was Sir Peter's opinion that Heathrow and Gatwick would run out of capacity during the 1980s unless something was done. He was only incorrect in that more breathing space was wrung out of the system but maybe the crunch is happening now.

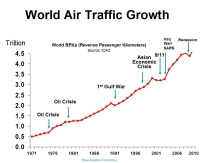

The worldwide civil aviation business has grown at an average 5% a year since the 1950s and continues to do so. There are occasional recessions and wars which can delay the effects for a year or two but the trend is clear.

After the end of World War II the major UK civil airports were directly run by Ministry of Aviation. In 1966 Heathrow, Gatwick, Stansted and Prestwick were grouped together to be run by a separate organisation, the British Airports Authority, under the chairmanship of the then Peter Masefield. Edinburgh, Glasgow and Aberdeen airports were added later. Southampton joined much later. Masefield was convinced that the third London airport should be Stansted, then a small public airport with a large runway built for the American air force.

After the end of World War II the major UK civil airports were directly run by Ministry of Aviation. In 1966 Heathrow, Gatwick, Stansted and Prestwick were grouped together to be run by a separate organisation, the British Airports Authority, under the chairmanship of the then Peter Masefield. Edinburgh, Glasgow and Aberdeen airports were added later. Southampton joined much later. Masefield was convinced that the third London airport should be Stansted, then a small public airport with a large runway built for the American air force.

Continuous controversy resulted in the Roskill Commission which was to consider all possible sites. Roskill gave the government a choice of four: Cublington – not a million miles from the current HS2 track in Buckinghamshire; Nuthampstead, Hertfordshire; Thurleigh, Essex, and Foulness, later called Maplin for obvious reasons after sands slightly further south, but still north of the Thames in Essex.

The Commission plumped for Cublington following a detailed cost/benefit analysis. There was a dissenting opinion by the transport planner Sir Colin Buchanan who favoured Maplin.

Maplin

Edward Heath’s Conservative government decided to back the Maplin option. Detailed studies had quietly started in July 1971 and on 28 September 1972, the first meeting of the confidential Maplin Project Management Committee was held under the auspices of the Department of the Environment to co-ordinate the work.

Edward Heath’s Conservative government decided to back the Maplin option. Detailed studies had quietly started in July 1971 and on 28 September 1972, the first meeting of the confidential Maplin Project Management Committee was held under the auspices of the Department of the Environment to co-ordinate the work.

A wide range of studies were commissioned but a major obstacle was seen as the moving of the military firing range from Shoeburyness, east of Southend and clearing the site of projectiles. The Ministry of Defence were less than enthusiastic but eventually a civilian workforce of some 200 people were engaged on the clearance work. The likely location of the replacement range was Tain in Scotland.

It was decided that it was only necessary to clear the sands to a depth of 1.5 metres as tests on Concorde and VC10 aircraft had optimistically shown that, with concrete and the fill on top of the sand, the vibrations of landing were unlikely to disturb anything that had penetrated further down. The Boeing 747, just entering service, let alone the undreamed-of Airbus A380, were not mentioned.

The Maplin Development Authority, tasked with reclaiming the 30 square miles of land required for the new airport and sea port, held its first official meeting on 6 November 1973. The Chairman, Sir Frank Marshall, said in his only annual report that the investigations had indicated that it was ‘an area exceptionally suitable for reclamation at a lower cost than was previously envisaged’. The Dutch were particularly helpful with their experience in such matters.

Once the land was reclaimed it was to be handed to the British Airports Authority to construct the airport and to the Port of London Authority (PLA) to build the accompanying sea port.

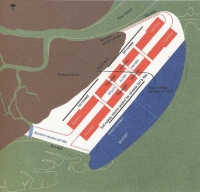

Norman Payne, then Chief Executive of the British Airports Authority, announced broad plans for the airport in March 1973. When it opened, it would have a single runway and one terminal but, by the late 1990s, the plan was for four runways, each of 4,250 metres, and 10 terminals arranged as a spine between the runways.

Norman Payne, then Chief Executive of the British Airports Authority, announced broad plans for the airport in March 1973. When it opened, it would have a single runway and one terminal but, by the late 1990s, the plan was for four runways, each of 4,250 metres, and 10 terminals arranged as a spine between the runways.

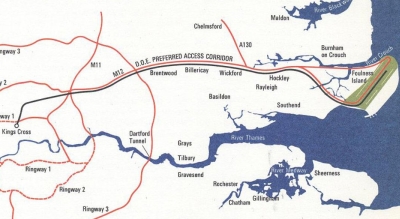

Access would be by a non-stop rail service from Kings Cross, taking just 40 minutes. There would be a motorway link from the planned London Ringway (subsequently abandoned but parts would become the M25) and both the road and the railway would enter the spine of the airport from the south and later continue from the north end of the site. The airport would handle 32m passengers annually by 1986 and 120m when completed in the late 1990s.

Cost estimates at the time produced figures of around £1,000m for the entire project, including urbanisation, by the 1990s.

Aircraft would approach and depart entirely over the sea. There would be 400 houses within the 35NNI noise contour as opposed to 250,000 at Heathrow.

The PLA had identified the potential of Maplin a decade earlier and had extended its area of responsibility to include the site. It had seen the need for a major deep-water container port and a terminal for super-tankers and was eager to start construction. The reclaiming of 30 square miles at Maplin was just part of its broad plans to reclaim some 300 square miles along the Thames estuary.

Problems

Problems arose in October 1973. As a result of the Arab-Israeli Yom Kippur war, the price of crude oil soared from US$3 a barrel to US$12 (or US$60 at 2011 prices – today’s price is around US$129 a barrel). By March 1974, petrol prices at the pump had risen 70% and the first fuel crisis was in full swing.

In February 1974 there was a general election which resulted in a hung parliament with Labour forming a minority government under Harold Wilson. Various reviews were undertaken and on 8 May 1974, the Department of the Environment wrote to the Maplin Development Authority instructing them not to incur further costs and to plan to shut down by 30 June. The Cabinet confirmed the cancellation at their meeting on 16 July 1974.

Curiously the sea port was not mentioned in the cancellation and even in 1976 the PLA was still hoping that it could be developed.

And what if it had happened?

If Maplin had gone ahead, what would have been the consequences?

First, Stansted and Southend airports would have closed completely and would probably have been turned over for housing or industrial estates. Development of Luton airport would have been curtailed and much of its traffic would have moved elsewhere. Manston would probably have shut when the RAF moved out. Development at Heathrow would have stopped at three terminals and two runways and Gatwick would have remained with a single terminal and one runway. Their aircraft movements would be capped at 1980 levels.

First, Stansted and Southend airports would have closed completely and would probably have been turned over for housing or industrial estates. Development of Luton airport would have been curtailed and much of its traffic would have moved elsewhere. Manston would probably have shut when the RAF moved out. Development at Heathrow would have stopped at three terminals and two runways and Gatwick would have remained with a single terminal and one runway. Their aircraft movements would be capped at 1980 levels.

In 1980 Heathrow handled 294,619 aircraft movements (479,100 in 2011); Gatwick reached 143,522 (246,600 in 2011). West London and north Sussex would have been around 40% quieter now.

With a major seaport at Maplin, Felixstowe docks would not have happened, and port development on the Thames estuary may have been different.

One could surmise that London’s development towards the east would have happened sooner and, without the major airport expansion at Heathrow, there might have been less urban growth in west London and along the M4 corridor as well as the Crawley/Burgess Hill area. East Anglia would have seen much more progress, especially in Essex. By the 1990s the staffing requirement may well have topped 60,000.

The significant question is whether the airlines would have used Maplin? Moving the infrastructure of a home base is hugely complex so UK airlines would have faced serious decisions. Overseas carriers rarely consider a particular route more than a season or two ahead so they are more flexible – note how quickly current low-cost airlines start-up and stop services. However, the large scheduled carriers prefer to work on the honeypot principle and swarm in one place even if facilities are better elsewhere.

Alternatively, airlines will always go where they think they can make money. If there is enough traffic, someone will operate an air service.

In the 1970s the government was enthusiastically interfering in business decisions. After the cancellation of Maplin it attempted to move all the Canadian and the Iberian air traffic, including British Airways, from Heathrow to Gatwick. That was only avoided by a general election. It did insist any new airline wanting to serve London should use Gatwick and not Heathrow, just at the time US airlines were expanding into Europe. Today, those airlines have disappeared or squeezed into Heathrow and there are now few major overseas scheduled carriers serving either Gatwick or Stansted.

The panic caused by the escalating oil price rise did not last. Air passenger figures for the London area peaked at 29.41m in 1973, dropped by two million in 1974 and were back at 31.03m in 1976. In 2011 the six London area airports handled a total of 133.62m, nearly 14m more than the planned capacity of the completed Maplin.

David Hurst davidhurstassocs@aol.com

OUR READERS' FINEST WORDS (All times and dates are GMT)

All comments are filtered to exclude any excesses but the Editor does not have to agree with what is being said. 100 words maximum